The Paris 1924 Olympic Games were a spectacular event.

It was the first time, an Olympic Village for athletes was built, and the Olympic motto Citius, Altius, Fortius (Faster, Higher, Stronger) was introduced.

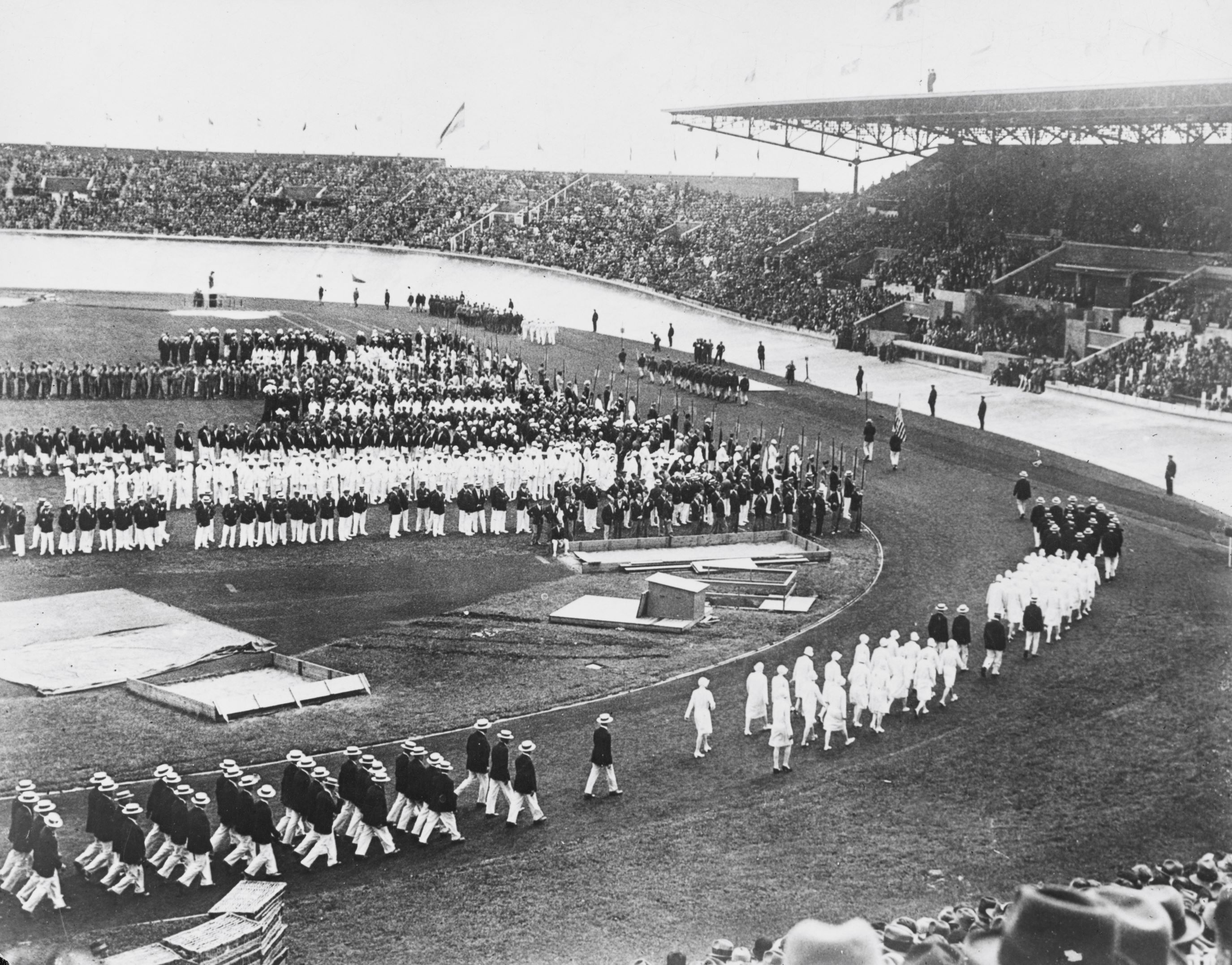

Forty-four countries took part in the opening ceremony at Stade Colombes, which held a huge 45,000 spectators. The stadium, now named Stade Olympique Yves du Manoir, will host hockey at the 2024 Olympics.

The star of the 1924 Games was Paavo Nurmi, the Flying Finn, who won five gold medals including the 1500m and 5000m within 75 minutes of each other. Another huge name was American swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, who won three gold medals, and a bronze in the water polo. Weissmuller, who never lost a race in his career, eventually gained greater fame as Tarzan in Hollywood movies.

Eric Liddell, who had played rugby for Scotland, won the 400m in world record time. He was was a leading figure in the film Chariots of Fire.

French sports fans revelled in the feats of fencer Roger Ducret, who won five medals, three gold.

Three American women stood out – tennis players Hazel Wightman and Helen Wills and swimmer Gertrude Ederle. However, it’s worth noting that of the 3088 athletes at the Paris Olympics, and only 135 were women.

In 2024 the New Zealand Team is expected to number more than 200 athletes.

It’s a far cry from 100 years ago when we named just four athletes to compete at the Olympic.

Runners Arthur Porritt and Randolph Rose, swimmers Gwitha Shand and Clarrie Heard, boxer Charlie Purdy and a rowing eight “if sufficient funds are available”.

In the end only Porritt, Shand, Heard and Purdy attended. For Porritt, the trip from London was not too onerous, but the other three New Zealanders had to undertake a demanding and time-consuming round-the-world voyage to get to France.

Only Porritt, with his shock bronze medal in the 100m, excelled.

Lightweight boxer Purdy faced a tough proposition against Frenchman Henri Tholey in his opening bout. Though Purdy looked to have won the first two rounds clearly, he lost the fight on a 2-1 vote. The deciding vote went to the French referee, whose decision was greeted with acclaim by the partisan crowd if not spectators from outside France.

The swimming pool was 50 metres long for the first time in Olympic history and was built on massive concrete pillars three storeys high. Furnaces burned under the pool to heat the water.

Heard had an unusual Olympic experience. He was swam well below his best in his 200m breaststroke heat, but was 12th fastest overall, which seemed good enough to advance to the semi-finals. Bizarrely, he was not granted a semi-final spot – six swimmers contested the first semi and five the second!

Shand, suffering from a cold, won her 400m freestyle heat, was third in her semi-final and withdrew after 300 metres of the final. It was a pity she was not in good health – she was a world-class swimmer.

In a lifetime of achievement, Arthur Porritt was:

Governor-General of New Zealand from 1967-72

- A life member of the International Olympic Committee

- Made an Officer of the US Legion of Merit for his service in World War II

- Surgeon to the Royal family for more than 30 years

- Knighted, and then made a Baron.

Yet, as he once reflected: “I was most remembered for something I did in less than 11 seconds in 1924.”

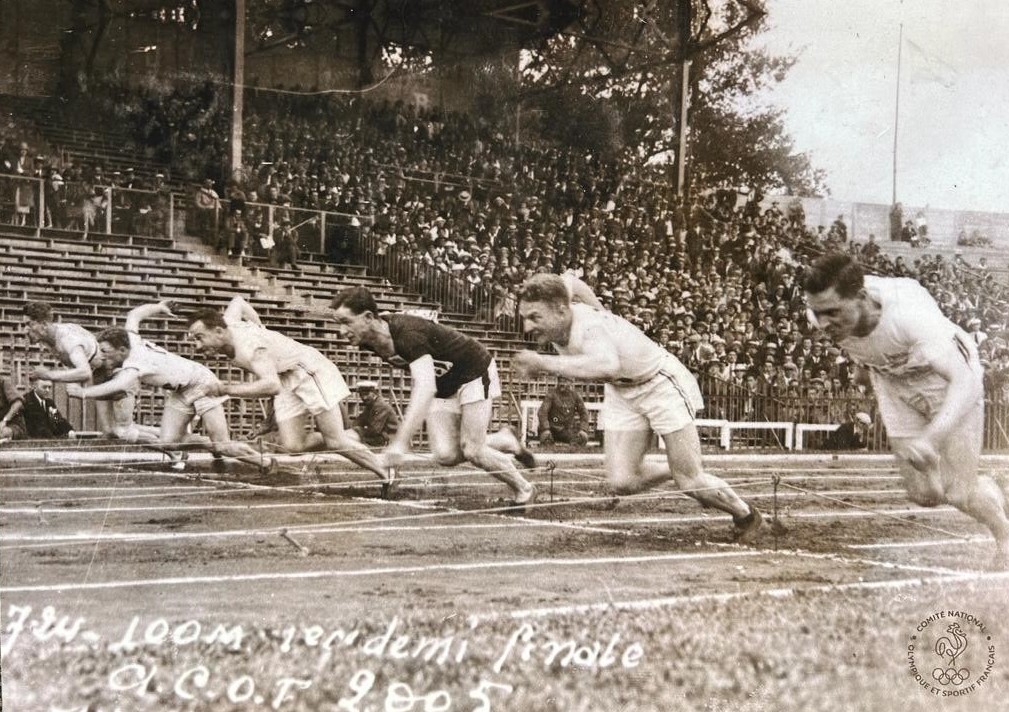

Porritt, a rank outsider, finished third in the men’s 100m at the 1924 Paris Olympics, a race made famous because it was the centre-point of the 1981 Academy Award-winning film Chariots of Fire.

“Even when I was Governor-General I was chiefly remembered for that Olympic medal.”

Porritt was the best New Zealand sprinter of his time, but felt he was chosen for Paris chiefly because he was living in England – studying medicine at Oxford University. He was named team captain.

He was very close friends with sprinter Harold Abrahams. “Harold used to beat me most weekends at events all around England.”

In Paris, Porritt shocked himself by finishing second in his first-round heat. He was second again in the next round and so advanced to the semi-finals, to his great surprise.

In the semis he edged into second place to qualify for the six-man final.

“I couldn’t believe it. I thought that even if I ran backwards and came last in the final, I was sixth in the world!”

The final progressed as Porritt expected and he trailed the field at the halfway point. Then he found a burst of speed and with a desperate thrust at the line, finished third behind Abrahams and American star Jackson Scholz.

Baron Pierre de Coubertin presented the medals.

Porritt always cherished the memory of that race, which was why when Hollywood producers came to him in 1978 to tell him they were making a film based around that final, he asked that his name not be used.

When Chariots of Fire was produced, the New Zealander in the outside lane was called Tom Watson.

“Imagine what I felt when I saw the film. I thought it would be a tawdry Hollywood effort, but it was magnificent and I would have been proud to be in it. It was one of the biggest mistakes of my life.”