Precious McKenzie was born in Durban, South Africa, in 1936 and won three Commonwealth Games weightlifting gold medals for England before throwing in his lot with New Zealand.

The impish, wise-cracking McKenzie captured the hearts of New Zealanders when he competed at the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games. He won the bantamweight gold medal for England, his third consecutive Games gold. And he still wasn't finished.

Four years later in Edmonton he won again, but this time wearing New Zealand colours.

“I was offered employment while I was in New Zealand in 1974,” he said. “Back in England, I was working in the shoe industry, and that's the line of work I was offered here. But at that time I was looking to do some work in gyms, so when Suckling Brothers of Christchurch offered me work, I turned it down.

“I did love New Zealand, though. The people were so friendly and I had a great time.

“Later in 1974 I came back to compete in a Commonwealth v New Zealand weightlifting competition at the Trafalgar Centre in Nelson. When I arrived, I was met at the airport by television. I was asked why I'd refused the job offer. It was a direct question and I said I wanted to be a coach. I said I was ready to work for any sports centre that required my services, that I was ready to immigrate.”

McKenzie in effect was given a prime time television advertisement for “Jobs Wanted”. Not surprisingly, he received several job offers.

“I had a look at one in Wanganui, then took at job at the Panmure Youth Citizens Centre. There were more people there to work with. Don Rowlands, the rowing administrator, was the man behind getting me to Panmure job.”

So McKenzie and his wife, Elizabeth, moved in 1975. They wanted to leave England because they detested the cold weather. It wasn't very long before they thought of themselves as New Zealanders. Their two boys were born in South Africa and their daughter in England.

“Before we arrived in New Zealand we lived in Bristol. When we left South Africa in 1964, we moved to Northampton, and then I got redeployed to Bristol. When we moved there, the neighbours saw we were black and hoped we wouldn't buy a house there. They avoided us at first.

“Those same people later saw me on television and began to boast about me. They eventually became friends, but some things never change. When I was leaving, they told me they hoped my house wouldn't go to Italians!”

McKenzie left South Africa because he knew that as a coloured, he'd never be able to represent his country happily at weightlifting.

“The National Government there made it very clear no black would be allowed to represent their white country. I was excluded from the 1958 Empire Games team and the 1960 Olympic team because of apartheid. I was told I could represent South Africa at the 1964 Olympics, provided I was segregated from the white members of the team, so I refused.

“It's no good being the best weightlifter if you can't prove it, so we left. When we arrived in England I had £95. I loved England because they accepted me as me regardless of my colour.”

McKenzie prospered in England. He won gold medals in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1966, Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1970 and, of course, Christchurch in 1974. He represented Britain at the 1968, 72 and 76 Olympics, finishing 9th, 9th and 13th. He was awarded an MBE, became a friend of the Royal Family, wrote a book, attended Olympics and world championships and became a television personality.

“I loved winning for England. I felt proud. But I was also very happy to move to New Zealand. We have enjoyed our time here so much.”

The first New Zealander McKenzie met was giant weightlifter Don Oliver. “I was walking in the Games village in Kingston when I saw him. We shook hands and remained good friends for the rest of his life.”

But that wasn't the first time he heard of New Zealand.

“We were taught about New Zealand at school. But what we were taught was all wrong. They told us Australia and New Zealand were colour-bar countries. I was surprised when I came here and found it was a multi-racial country.”

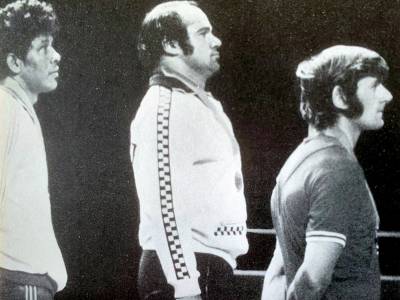

Though exceptionally short – 4ft 10in or 1.47m – McKenzie was the dominant Commonwealth lifter in his class, at least until Edmonton in 1978, when he was 42. But that year, when he desperately wanted a fourth gold because it would also mean a gold for his new country, he found himself in deep trouble in the bantamweight contest.

“My preparation that year was my best ever and I'm sure I would have walked in normally. But I cramped very badly during the contest.

“All along I knew I was slightly lighter – 80 grams – than my chief opponent, Tamilsalvan of India.

“I was struggling just to lift because of my cramp. But I fought on and when it came to my last lift, I decided to go for a total that would equal his. It was a risk because he had another lift remaining. But I wanted to at least put him under pressure on his last lift.

“If I'd missed my last lift, he would have won. And even if I got it right, he could go up another weight and beat me. I had to get it and I did. Then he made a bad mistake. He tried to lift too much. He should have gone up 2.5kg, but he went up 5kg. I don't know why. Maybe he was going for a record. Well, he missed that last lift and I won the gold.”

McKenzie said it was a big relief. Normally with cramp that bad, he'd have given up, he said.

The little lifter rated his first gold, the moment he proved himself to the world, and that fourth one, as the most special.

“The Kingston Games was my first international competition, though I'd been lifting since 1957, when I was 18. Before that I had wanted to be a circus performer. When I stood on the dais with the gold medal around my neck and heart the English national anthem playing for me, I was dazed.

“In school I'd heard that anthem, but I never dreamed it would play for me. I thought, ‘Why is the world so cruel I can't represent my country, but another country opens its arms for me?' What hit me then was how proud I was to win for England.”

The moment of his life, though, was receiving an MBE from the Queen in 1974, the year he featured on the This Is Your Life television programme.

“I came from a very, very poor upbringing. I had two bothers and a sister. My home was in Pietermaritzburg, but we grew up in Cape Province. I was brought up in a Catholic convent. My father died when I was a baby and my mother had to work, so I went into a convent.”

He was called Precious because he was such a sickly child. “I had double pneumonia and when I survived they called me Precious.”

If ever there was a story of a man fighting against the odds, this is it. Because of his ability and charisma, McKenzie prospered.

In England he worked in prisons and on television. In New Zealand he worked first at Panmure, and then for the Les Mills Fitness Centres for six years from 1980.

He made one particular contribution to New Zealand fitness. “Colleen Mills and I started aerobics classes to music. We introduced them to New Zealand, though I'd started classes to music with seven girls and my wife in South Africa in my dining room. When I got to England I ran jazzejetics classes.”

In 1986 McKenzie tried running his own gym, in partnership with Mills and Bruce Cameron, but the venture was only a partial success. Then he set up Precious McKenzie Promotions to run back-injury pr

Tweet Share

Precious's Games History

-

Commonwealth Games Edmonton 1978

- 1